Tempo Runs

Tempo runs are also known as lactate threshold runs–this is the point at which your body is unable to recycle accumulated lactate in the blood. This is a pace that’s anywhere between ten and 30 seconds slower than a 5k or 10k pace.

The goal of tempo runs is to increase your anaerobic threshold, thus allowing your body to sustain an effort that was previously unsustainable. This training technique tends to benefit longer-distance runners more than sprinters.

Tempo runs should be part of a weekly running routine, and can vary depending on experience level and training needs. One way to incorporate this into training is to start by running 15 - 20 minutes at 75% of maximum heart rate, then build up to 30 - 45 minutes by adding about five minutes to these runs weekly.

Strength Training

While many runners are laser-focused on logging miles, time in the gym can lead to time off your mile splits.7

Two areas of strength training are often employed by runners: leg and core workouts. Weight training can both improve strength and lead to greater running economy (as it did for female runners in this study).8

Exercises like lunges and squats can strengthen those leg muscles used more frequently on runs. And for core workouts, even simple additions like planks and leg raises and weighted sit-ups can positively impact form and posture. Don’t discount yoga and stretching–on days where you’re looking for some active recovery, yoga is perfect for both developing strength in core muscle groups and stretching tight muscles.

Fix Your Form

Essential to running efficiently, improving running form and technique can lead to faster speed. The way you run affects the way force is applied to your muscles and joints. Correcting form can be help injury prevention, as improper execution can cause injury if you’re a beginner;9 if you aren’t running, you aren’t getting faster.

“People assume that running is running is running, but it's not true. Especially when we sit at our desks all day, or aren't used to it.” — Michael Brandt, HVMN Co-founder and COO

Good overall form can feel like a unicorn; it’s best broken down into a few manageable techniques to consider on each run.

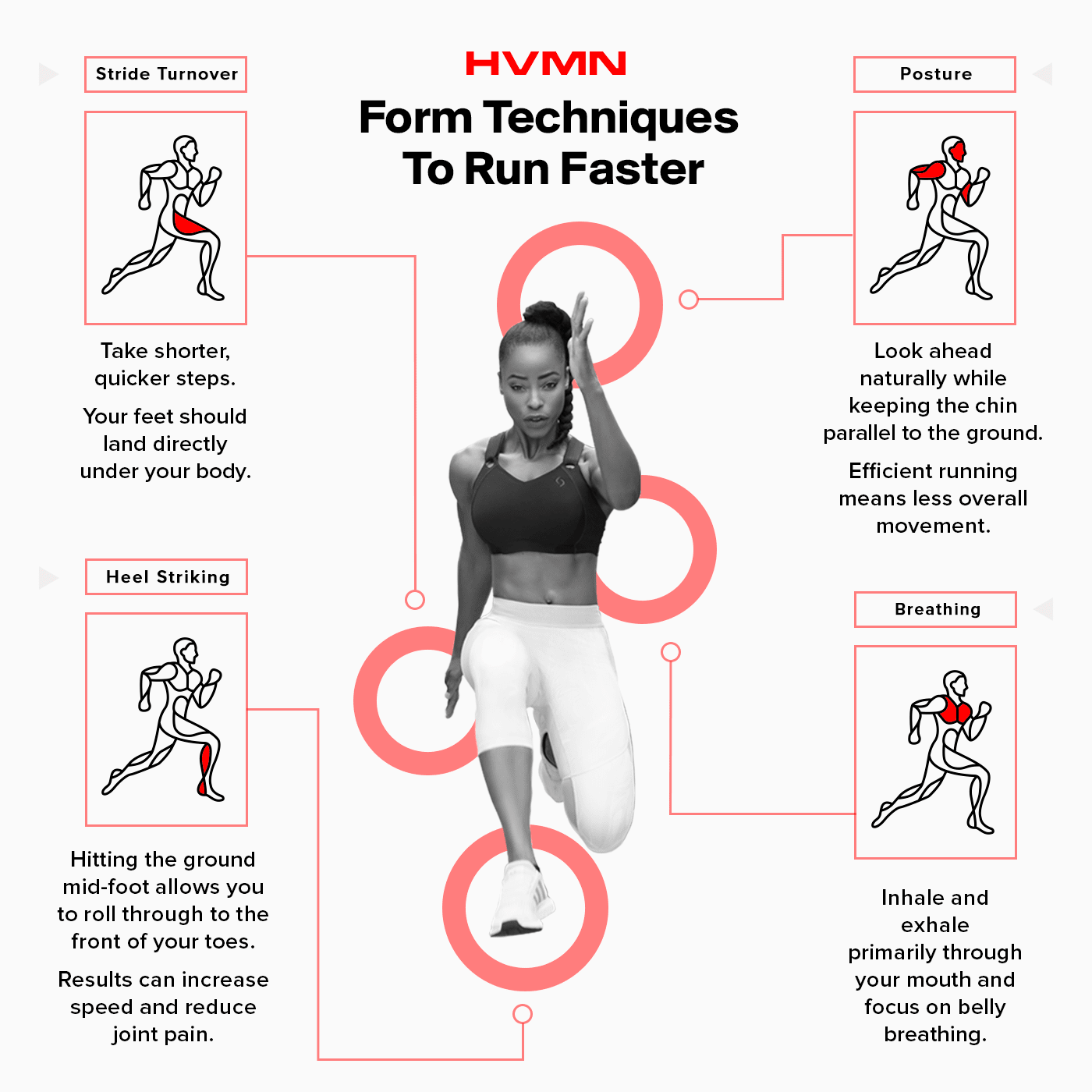

Stride Turnover

Changing stride turnover–how my steps taken during one minute of running–may have an impact on speed.10

The goal is to have a higher stride turnover, meaning to take shorter, quicker steps; these reduce the impact on your joints because you’ll hit the ground with less force. Longer strides have the opposite effect, and can create more impact because you’re in the air for longer. Sprinters will typically need to lift their knees higher to achieve maximum leg power, but distance runners won’t need as much lift.

Figuring out your stride turnover is easy. Just run for one minute at your 5k pace and count the number of times your right foot hits the ground. To improve stride turnover, jog for one minute to recover, trying to increase your stride count by one. Repeat this several times with the goal of increasing strides each time.

At the proper stride length, your feet should land directly under your body. And when your foot strikes the ground, your knee should be slightly flexed, bending naturally to the impact. Keep in mind that the middle of your foot should be making contact with the ground–not your heel.

Heel Striking

It’s a very common problem for runners.11 Landing on your heel can mean too long of a stride, which wastes energy and may cause running injuries (hello, shin splints).12 Avoid landing on toes too–this can also increase fatigue and wear out your calves.

You want to be a mid-foot striker. Hitting the ground mid-foot allows you to roll through to the front of your toes. Changing your footstrike takes practice, but the results can show up both in speed and in reduced joint pain. One study of runners from habitually barefoot populations showed an increase in speed when mid-foot or front-foot striking.13

Overstriding is usually the culprit–try increasing your number of strides. Your next run, focus on striking on the balls of your feet. Interestingly, that’s where most people strike when running barefoot; try running on grass (or another soft surface) without any shoes on, translating that muscle memory to other runs. Also, running drills can help. Skipping, high knees, side shuffling, butt kicks–with all these, it’s almost impossible to land on the heel.

One last thing. It may seem obvious, but keep those toes pointed in the direction you want to travel. As fatigue sets in, form gets wonky–you may find your toes are turning in or out, which can lead to joint pain.

Relax

It goes from top to bottom and will have an impact on running posture.

Relax your shoulders. Relax your arms. Relax your hands.